There’s been a ton of talk lately about how important the hip and ankle are to knee health.

There’s been a ton of talk lately about how important the hip and ankle are to knee health.

And I’ve done a lot of the talking, so trust me, I don’t disagree with this sentiment!

A smart approach to knee assessment and training will absolutely include looking at the entire kinetic chain, and especially the hips and ankles.

But have we taken this sentiment just a little bit too far?

It’s not uncommon for the pendulum to swing too far one way or the other.

15-20 years ago, I think we probably focused too much on the knee.

But nowadays, I think we’re looking too much at the joints above and below. As a result, we’re failing to properly assess and train the knee.

Let’s examine the knee joint a little bit more in-depth. We’ll start with an isolated approach to assessment, and then see how we can put all the pieces of the kinetic chain back together to develop a killer program that will help bulletproof those knees!

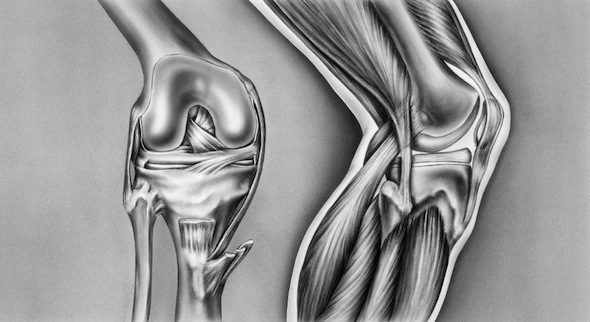

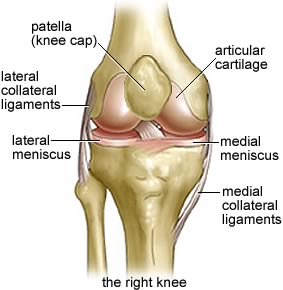

Knee Anatomy & Assessment

Something we probably all learned in Anatomy 100 class is that the knee is a hinge joint, blah blah blah.

Something we probably all learned in Anatomy 100 class is that the knee is a hinge joint, blah blah blah.

But here’s the bad news – the knee is not a hinge joint!

Instead, the knee is a condyloid joint. It moves primarily in one direction (flexion/extension), but also has a small rotary component when the knee is flexed.

When assessing the knee, the most obvious examination should start with flexion and extension. If you don’t have adequate flexion/extension, we can look up and down the kinetic chain for more clues.

To assess knee extension, have the patient/client lie on their back on an assessment table and relax. Place one hand just above the knee cap and hold the femur in place.

From this position, use the opposite hand and grasp just behind the Achilles tendon. A knee with normal mobility should have approximately 5-10 degrees of extension past neutral, with a soft end-feel.

If your client lacks this 5-10 degrees of extension past neutral, or the end-feel is abrupt of hard, this is a red flag.

To assess knee flexion, the patient/client lie will stay on their back on an assessment table. Grab the knee you will be assessing with one hand to stabilize the femur, and then use the opposite hand to move the ankle towards the buttocks.

A knee with normal mobility should have 135-140 degrees of flexion, with a soft tissue approximation end-feel. Essentially, you should feel as though you’re bumping into muscle on the back side.

One thing I’d like to note is if you evaluate very large or heavily muscled individuals, it may appear as though they are lacking knee flexion because they have a lot of muscle on the back side. This isn’t necessarily an issue, but something you need to be aware of.

Now you’ve evaluated the knee, and maybe you found a knee flexion or knee extension limitation.

The question becomes – is this a local (knee) problem?

Or something indicative of the entire kinetic chain being out of whack?

Let’s look at how we can piece all this together to get a more global perspective on how this client moves.

The Kinetic Chain Game

So our knee tests abnormally – what can this tell us about someone’s posture and alignment?

When starting an assessment, I like to use a static postural assessment to get a feel for what issues this client may have. While many are quick to write off a static posture assessment, I would argue that it’s only one tool in our assessment toolbox.

Used as a stand-alone, it’s probably not that effective.

But as a starting point for a more thorough assessment, I think it fast tracks us if you know what you’re looking for.

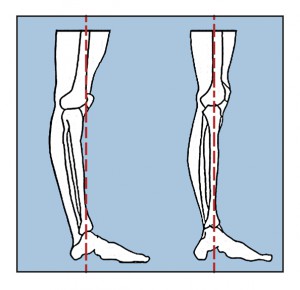

When someone presents with a hyperextended knee, look up the kinetic chain. Often times this is associated with an anteriorly tilted pelvis, coupled with an increased lordosis on the same side.

Here’s the problem with this – it’s not what I would call authentic, or clean, extension of the knee. Instead this is a compensation that needs to be addressed.

And even though the knee is hyperextended, it’s not necessarily due to strong or stiff quads.

In fact, the quads are often weak. This client is literally just hanging on their connective tissue to keep their knee in place.

On the flip side, someone with a flexed knee in their static posture will often present with a posteriorly tilted pelvis and an extended hip.

So if you find an issue in isolation as well as during their static posture assessment, you have a problem, right?

Maybe. But maybe not.

You know there’s an issue at the knee, but is it the issue?

Or, is their alignment issue driving this poor knee function and alignment?

To do this, you need to restore neutrality to the pelvis first. At IFAST we like the resets put forth by the Postural Restoration Insitute (PRI), but you could also opt for DNS, PRRT, or any other system out there that gets someone back to neutral.

Once you’ve normalized pelvic position, stand them up (or lie them back down) and re-test.

If the knee tests normal and static posture is improved, chances are you have a pelvic alignment issue that needs to be addressed.

And if you get them to neutral through the pelvis and the knee still tests abnormally, you’ll need to do some specific work to fix the local issue.

Now that we’ve taken a look at testing and alignment, let’s bring this together with some practical application.

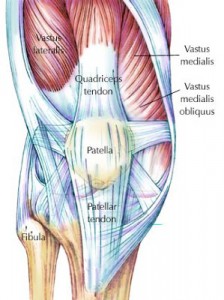

Should We Train the VMO?

Let’s say we’ve assessed someone and determined the have a local issue, in this case poor knee extension. A lot of people out there would say you need to strengthen their vastus medialis obliquus (or VMO) to fix the issue.

And while I’m not one of those that has ruled out the importance of the VMO, I would argue that we’ve probably been barking up the wrong tree with regards to maximizing it’s performance.

First and foremost, let’s get this out of the way:

I don’t think we need to strengthen our VMO whatsoever. Instead, we need to focus on timing.

I don’t think we need to strengthen our VMO whatsoever. Instead, we need to focus on timing.

To better understand this, look at all the research on the transversus abdominus (TVA) and people in back pain. I think we can all agree that the TVA probably plays some role in low back pain, but again, it’s our viewpoint of the muscle which needs to be re-examined.

(Side note/tangent: This is also true of the multifidi, diaphragm, and pelvic floor, so please don’t think TVA is the only important muscle group when it comes to core/trunk stability!)

However, nowhere in the research does it talk about TVA being weak.

Instead, it says there is a timing issue that needs to be addressed. So please, let’s stop all this drawing-in nonsense ASAP.

I think the VMO (a key knee stabilizer) works a lot like the TVA. It’s not so much a strength issue; instead, it’s a timing issue.

I think the VMO (a key knee stabilizer) works a lot like the TVA. It’s not so much a strength issue; instead, it’s a timing issue.

So the question becomes, what alters timing or firing of the muscles?

As you can see in this study by Van Tiggelman et al., subjects who developed PFP had a delayed contraction of the VL versus the VMO.

But the better question is, why did this happen?

What caused the timing to change?

I can think of two primary reasons:

- An issue (acute or chronic) that results in pain. As the saying goes, pain changes everything. Or,

- Altered feedback from the joint.

Now I’m not a medical professional, physical therapist or doctor, so if pain is altering things, you need to get that addressed first.

But if you fall into the second camp, and you believe what guys like Gray Cook and Charlie Weingroff tell us, you have to give stabilizers the foundation to be successful.

Stabilizers should work reflexively. If the joint is in the right place (alignment), and it can demonstrate normal mobility in all planes of movement, you have the foundation for optimal proprioceptive feedback.

The equation may look something like this:

Good Alignment + Good Mobility = Good Proprioceptive Function

Which then leads us to the following conclusion:

Good Proprioceptive Function and Feedback = Good Stabilizer Function

The old-school treatment program would be to try and “isolate” the VMO with exercises like terminal knee extensions in an effort to improve VMO recruitment and firing.

But maybe we’re looking at all this backwards.

Instead of trying to “turn on” a stabilizer (which should fire reflexively and without conscious thought or recruitment), maybe we should just focus on restoring optimal mobility and alignment first, and then letting the stabilizer do it’s thing naturally?

Going back to the knee study above, did the VL just magically start to fire first?

Or did something happen to alter proprioceptive feedback to the knee itself, which then altered firing patterns?

What I’m getting at here is this:

Normal knee alignment and mobility in the sagittal plane is a critical first step in optimizing knee function and biomechanics.

Of course we need to address the joints above and below, but if you have a local knee issue, that needs to be addressed along the way as well.

Summary

If someone’s goal is to optimize knee biomechanics and health, by all means evaluate the joints above and below. The lumbar spine, pelvis, hips, ankles and feet can all influence alignment and function of the knee.

But in the course of your assessment, remember the fact that the knee works primarily in the sagittal plane. And as such, it’s alignment, mobility and function in the sagittal plane is a critical piece of the puzzle.

All the best

MR

P.S. – Don’t forget, knee week is almost over!

You have until midnight, EST on Friday, April 19th to save 15% on either the Bulletproof Knees manual, or Bulletproof Knees and Back DVD Series.

Don’t delay, pick up your copy TODAY!