A few weeks back, my article 10 Nuggets, Tips and Tricks for Energy System Training got some great reviews.

A few weeks back, my article 10 Nuggets, Tips and Tricks for Energy System Training got some great reviews.

However, I don’t feel as though people should take what I say as gospel, either. There was one comment in particular from a reader that stood out:

Not that I’m against this style of training, I use it myself, but I always find the real improvements come through high intensity stuff.

When I was a LT in the Army I had my platoon do intervals almost every day with the occasional low intensity stuff and we had the top PT scores both individually and as a platoon in our brigade.

Since Jamieson wrote his book I keep seeing people bring this up, but I don’t see the improvements promised from the low intensity stuff alone.

There are definitely some things to think about in here.

Here are just a handful of counterpoints I would make – not to say the commenter above is right or wrong, but rather, to flesh out the discussion a bit and make sure we’re comparing apples to apples.

Point #1 – Aerobic Training is Not JUST low-intensity training

One of the big issues with regards to aerobic training is the thought that it must solely consist of long duration, low-intensity methods of training.

Basically, if it’s not “long, slow cardio,” it doesn’t count.

On the contrary, aerobic training can absolutely run the spectrum with regards to intensity level. In Joel Jamieson’s Ultimate MMA Conditioning book, he outlines eight different methods for aerobic energy system development.

On the contrary, aerobic training can absolutely run the spectrum with regards to intensity level. In Joel Jamieson’s Ultimate MMA Conditioning book, he outlines eight different methods for aerobic energy system development.

Just remember that as long as you’re under anaerobic threshold and relying on the aerobic energy system for the bulk of your energy demands, you’re doing “aerobic” training.*

(*Remember, the second you start training, you’re activating all of your energy systems at once. The intensity and duration will ultimately determine which “system” is used the most.)

So instead of focusing solely on long-duration, low-intensity exercise, think instead about the spectrum of aerobic development, from power to capacity.

Point #2 – We Must Define our Intervals

Another thing that’s important to note when talking about interval training is to define the intensity and duration of your intervals.

For instance, if you’re going with balls out intensity for 30 seconds on and 30 seconds off, you’re absolutely tapping into the anaerobic energy system.

First off, you’re going for an extended period of time (anything over 8 seconds and you’ve tapped out your ATP-CP system).

Combine that with the fact that you’re working on incomplete rest periods, and it’s obvious the anaerobic/glycolytic energy system is going to put in the lionshare of the work.

But that doesn’t mean that all intervals are created equally, or target the same system.

With many of my athletes I train what’s called “aerobic power” or “threshold training.” This style of training puts them consistently around their anaerobic threshold for an extended period of time (typically between 2-5 minutes), and then give them an equivalent amount of time off.

So the length and duration of your intervals must be discussed. Just because we’re doing “intervals” doesn’t mean we’re doing high-intensity interval training, or glycolytic/anaerobic intervals.

Point #3 – Anaerobic Training is Easy to See Progress With

This is where things get interesting.

I often allude to anaerobic training as the “icing on the cake.”

If you’ve put in the work and have some modicum of an aerobic base, you can see huge progress in your high-intensity conditioning levels rather quickly.

The first question I would ask is this:

In the Army, does your platoon already have an aerobic base? I would assume so, but you know what it means to assume!

Think of it like this: If your guys have been doing training runs and have already achieved a minimum standard of aerobic development, this could explain why they saw such huge improvements in performance.

Again, it’s like putting the icing on the cake – they already had a strong aerobic foundation, so when you moved them to anaerobic development, it gave them a balance between high and low-intensity training.

Now let’s take that a step further.

Patrick Ward has an awesome presentation on the Power-Capacity Continuum that I’m reviewing now. In this presentation, he discusses how we can see shifts and improvements in anaerobic development in as little as one week (or 3 sessions) of training!

Anaerobic training absolutely looks and feels like you’re making more progress, and it’s because you probably have a smaller window of adaptation.

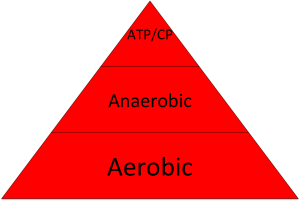

If we go back to our pyramid, just like we build from the ground up, we also need to consider our ability to adapt and build each energy system.

The aerobic energy system (base of the pyramid) has the greatest window, or potential, for adaptation. This is why damn near anyone can train and (eventually) run a marathon.

The aerobic energy system (base of the pyramid) has the greatest window, or potential, for adaptation. This is why damn near anyone can train and (eventually) run a marathon.

The aerobic energy system is very trainable, and has a huge window potential for adaptation.

Next is the anaerobic energy system. Here, our window for growth and development is much smaller.

And last but not least, the ATP-CP system is the top of the pyramid, with the least room for growth and development.

The bottom line is this: You can absolutely see huge changes in performance with you train anaerobically. But the gains will only come for a short period of time, and you don’t have the same potential for long-term development when compared to the aerobic energy system.

Point #4 – The Idea of Recovery Runs

You mention that you threw in some occasional low-intensity work from time-to-time. I’d ask how often/frequently you did this, because it could have had a huge impact on training and performance.

If your platoon had an aerobic base/foundation, and then you threw in occasional low-intensity work, that probably worked as a recovery modality first and foremost.

But it also (most likely) helped to mitigate any massive shift to more anaerobic changes. Remember that the aerobic and anaerobic energy systems directly compete with each other for adaptations throughout the body, so this low-intensity “recovery” work probably did a lot to keep your guys going strong.

My good friend Eric Oetter and I use to talk about energy systems development incessantly. The guy is brilliant, and a phrase he used to use was this:

“Keep the pathways open.”

Quite simply, if you’re going to do a block of high-intensity interval training, use some low-intensity work on off-days to blunt a massive shift to anaerobic development.

Keep those aerobic energy system pathways open, because you’ll never know when you’ll need to tap back into them!

Point #5 – Time and Dose High-Intensity Training Appropriately

Last but not least, I need to note that I’m not against high-intensity training – it just needs to be done at the appropriate time and dosage.

Too often I see people with no aerobic base whatsoever, who jump immediately into high-intensity training. This will ultimately limit their adaptations to anaerobic/glycolytic training, as they don’t have the aerobic base to support and recover from high-intensity work.

The anaerobic system is the last one you should be developing when it comes to energy system training – the proverbial “cherry on top.”

Furthermore, when you do start incorporating high-intensity training, I wouldn’t do it day-in and day-out for months on end. Remember, we can see improvements in this system in as little as 3 training sessions.

My goal when incorporating this kind of training for team-sports athletes is to do as little work as possible. Expose them to the stimulus and kick-start the adaptation process, but don’t do it so often or frequently that you start to see the conflicting adaptations with the aerobic energy system.

All the best

MR

(Lead photo courtesy of Fotopedia)