(Lead Photo courtesy of Keith Allison)

Derrick Rose is the elite of the elite.

A former NBA Most Valuable Player (MVP), the guy has a ridiculous amount of talent, and if he didn’t play for one of the Pacers most hated rivals, I’d have a total man-crush on him.

DRose has made waves recently, saying he’s even more explosive now than he was in the past.

And if you know anything about this guy’s game, he was already one of the most freakish athletes in the game.

In this ESPN article, Rose claims to have added five inches to his vertical jump while rehabbing from a torn ACL.

Five inches!

What would you do, as an athlete, with an extra five inches on your vertical?

When I first read that, my immediate reaction was “no way.”

An elite athlete who is already sporting a 37 inch vertical jump is now jumping 42 inches?

No way.

My immediate thought was there was some sort of testing issue initially. Like an intern didn’t measure his reach correctly, or something like that. (It’s always the interns fault.)

Someone who is competing at the highest level, and who is already in the most rarefied air when it comes to athleticism, no way could he add an additional five inches to his vertical.

But then all I could think was, what if this wasn’t a mistake?

What if he really did add five inches to his vertical?

The next question becomes, how did he do it?

Now my brain is really spinning.

I’m thinking about the possibility of all this, and how it could be done.

And I’m doing my best to talk myself into it.

Because that’s what performance coaches likes myself do – geek out over making an elite athlete even better.

Let’s take a quick look back at Derrick’s playing career, and then we can hypothesize* on how an ultra-explosive athlete just might have taken his performance to the next level.

(*That’s all this post really is – a hypothesis or “what-if” scenario. I’m not claiming to have any insider knowledge with regard to Derrick Rose’s training. Instead, this might be a fun, yet logical explanation of how all this would play out.)

Athletic Background

I’ve followed Derrick Rose since the end of his high school career.

The guy grew up in Chicago, and was the premiere talent in his recruiting class coming out of Simeon High School. Quite simply, everyone was in love with the humble, quiet kid from the Windy City.

Not only does he have an amazing skill set as a point guard, but he’s always been known for his explosiveness. The first time I watched him play at Memphis I was shocked at how quick he was when moving side-to-side, especially with the ball attacking the basket.

And – oh yeah – he can jump a little bit as well!

Don’t believe me?

Here’s a quick highlight reel to give you a feel for how explosive this guy is. And remember he’s only 6’3″, so he’s definitely on the shorter end of the NBA spectrum.

Rose played one year at Memphis, narrowly missing out on an NCAA championship. With the current NBA set-up where young men have to wait at least one year before joining the NBA, I think everyone expected him to be a one-and-done at college.

And that’s exactly what happened.

So D-Rose gets drafted #1 by the Bulls, and he’s been in the league ever since. A good friend of mine, Josh Bohnotal, was an assistant strength and conditioning coach with the Bulls early in Derrick’s career and had nothing but amazing things to say about him.

Down to Earth.

Hard working.

Driven.

All the tools you want in an athlete – and something you love having in your best player.

So here’s the starting point for my theory – on how he just might have added those five inches to his vertical jump.

Most high school athletes aren’t put into great strength training/physical preparation programs. I’ve seen this first hand myself.

Just because you’re an elite high school athlete or blue chip recruit, doesn’t mean you’re getting elite talent when it comes to performance coaching.

Instead, imagine being a 16, 17, or 18 year-old kid, and everyone and their brother wants to “train” you.

To get a piece of the action.

You’re not necessarily getting the best coaching, training or development. You’re simply working with the person who is the best salesperson.

And this is assuming he even had a strength or performance coach at that point in time!

My point here is this:

At 19- or 20-years-old, chances are Derrick hadn’t been coached much (if at all) on quality movement, nor had he had the time to develop a big strength base.

This could be the foundation for his improvement

If you’re working with an elite talent in any major sport, one of the biggest issues is time.

Competitive seasons are long. Even longer if your respective team is good and playing deep into the playoffs.

What’s worse? Off-season training programs are short.

It’s hard to do all the things you want to get done. To train all the various physical qualities.

The issue becomes, when do you have time to build a movement base?

When do you have the time to push the weights and get stronger?

Quite simply, you don’t.

Coming into the league, Derrick probably hadn’t had much time to really develop his body.

And once you’re in the grind of a year-long NBA schedule, you don’t have a ton of time, then, either.

When Derrick tore his ACL in the 2012 playoffs, everyone feared that he might lose some of his trademark explosiveness.

Yet now he’s come back more explosive than ever. How?

Vertical Jump Training

If I were training Derrick Rose (or someone like him), there are three things I would be focusing on:

- Movement quality,

- Building the posterior chain, and

- Strength.

Movement Quality

While following Derrick’s playing career, one of the things that seemed to be a consistent theme was anterior knee pain.

And again, I’m not his coach, nor have I ever trained him, but I could see this in his movement.

The guy was very explosive, but he was also very knee/ankle dominant in his movement. You could tell he had strong quads (as evidenced by his lateral movement and agility, and his vertical jump).

Every time he went to plant and cut, there was a lot of loading on his quads and knee joints.

This is a blessing and curse.

You can be explosive as hell, but you can also overload the quad/patellar tendon very easily, too.

During the shortened/compressed 2012 season, DRose had a rash of injuries.

A strained groin.

A sore/stiff lower back.

And of course the big knee injury.

When you start seeing a trend of injuries like that, you know something in the movement foundation probably isn’t right.

So the first step after ACL rehab (and really, during rehab) is to start cleaning up the movement base.

Getting the core online and strong would be Priority #1. The goal wouldn’t be to get a rock-star athlete out of anterior tilt/lumbar extension, but rather to give them the ability to better control it.

The core really is the centerpiece of the body. Without it, stability everywhere is compromised.

So that would be another big focus – stability.

It doesn’t look as sexy as a big power clean or squat, but if you can teach someone to better integrate, stabilize and control their core, pelvis and hips, you can make someone much more powerful.

This would be even more important coming off the injury. If you review the ACL tear video above, you can see the injury was non-contact (i.e. no one bumped into him or ran into his knee).

If you’re having trouble seeing this, pause it at the 1:00 mark. You can clearly see the knee caving in relative to the foot and hip.

Another key would be teaching them how to effectively load the glutes and hamstrings. This may sound simple, but you’d be shocked at how many athletes have no clue how to do this.

At the end of the day, this has to be the starting point.

Building capacity (speed, strength, power, conditioning) on top of a poor movement foundation leaves you continually exposed to undue stress, strain, and potential injury.

Remember, the key here is efficiency.

To give the athlete the ability to use the right muscles, at the right time, with an appropriate amount of strength.

This was what really got me thinking the five inch jump improvement could be legit. We’ve seen similar things happen at IFAST with our clients, albeit with lower caliber athletes.

When you get an athlete moving better, you make them more efficient. And more efficiency typically translates into more strength, speed, power, and/or explosiveness without training those specific physical qualities.

Quite simply, you give them their natural movement skills back.

This alone could be worth an inch or two on a vertical jump, no doubt about it.

Even with high caliber athletes, I’d argue most are leaving performance on the table as a result of how they move.

Which leads directly to my next point.

Building the Posterior Chain

Once the movement base has been developed, it’s time to get strong.

But more importantly, you want to get strong in the right areas.

As I mentioned up front, Derrick has always been appeared to be a quad-dominant athlete. And this is a huge part of what makes him special.

Read this next part twice, because it’s critical:

When training an elite athlete you don’t want to take away their natural talents and gifts, but you want/need to bring up lagging or weak areas to a more acceptable standard.

Building the movement foundation would improve an athlete’s core control, and should teach them how to access and load their posterior chain.

The next key would be to load the bejesus out of those glutes and hamstrings.

For many of my field sports athletes, we ration the amount of quad-dominant work we do in the weight room. They get so much loading during practice and games, there’s no use in beating a dead horse in the weight room.

I remember a podcast interview I did with Charlie Weingroff back in the day. Charlie was a former NBA strength coach with both the New Jersey Nets and Philadelphia 76ers, and he made a great point.

Charlie told me when training his NBA players his goal was to execute every lift in the weight room with a vertical tibia, making it very hip dominant.

And the proof is in the pudding – if I recall correctly, Charlie’s teams didn’t miss one single game due to patellar tendinopathy during his tenure as strength coach.

This is where you put the athlete on a steady diet of RDL’s, rack pulls, deadlift variations, and (possibly) even box squatting variations.

The best part is a lot of these can be used in conjunction with the ACL rehab. You kill two birds with one stone.

Not only will this help with performance on the back end (running faster, jumping higher, etc.), but it will also help protect the ACL in the future.

Now let’s look at the final piece of the puzzle: A focus on strength.

Strength Training

Last but not least, the big focus here would be on strength training.

Basketball players, by and large, are very reactive/explosive athletes.

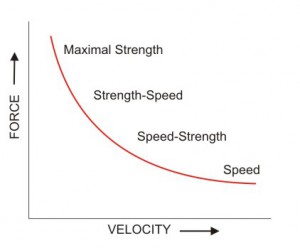

If you look at them on a force-velocity curve, they will trend towards the right-hand side.

If you look at them on a force-velocity curve, they will trend towards the right-hand side.

But rather than thinking about force/velocity, think about what tissues are being loaded the most on each side of this continuum.

When training for strength, you’re more focused on loading the muscle tissue. Movements are typically slower and more controlled.

This about a powerlifter who is grinding out a big squat or deadlift. His muscles are working over time to push through a sticking point and finish the lift.

On the other hand when training for power/explosiveness, you’re loading more of the muscle-tendon complex. You’re training your body to be efficient at storing elastic energy in those areas to make you quick and explosive.

Here’s the big takeaway:

Many reactive/explosive athletes like to lift weights like they play sports. They’re essentially bouncing the bar up and down very quickly. These athletes rarely (if ever) spend enough time on the left side of the continuum!

Basketball players are some of the most springy/elastic athletes you’ll ever meet. They can often jump out of the gym, but can’t squat their own body weight.

While you can’t train the muscle without the tendon (or vice-versa) you can preferentially recruit one over the other with smart training.

Making a concerted effort to slow them down and really load the muscles themselves can go a long way to making the actual muscles themselves stronger.

And as we all know, strength is the foundation for more power and explosiveness.

So maybe increased strength added another inch or two as well.

And just taking a year off from competitive basketball to rest and rebuild his body was good for one more.

So if Derrick Rose builds a movement foundation, and builds a serious posterior chain, and gets stronger, isn’t it possible that he really did add five inches to his vertical?

As a die-hard Pacers fan, this is scary to think about.

But maybe, just maybe, this is possible.

Summary

Two weeks ago, I got to see the Bulls play the Pacers during the first pre-season game.

While everyone was sporting a bit of off-season rust (especially with regards to shooting and finishing at the rim), Derrick Rose looked every bit as explosive now as I’ve ever seen.

And while I’ll be cheering for the Pacers every step of the season, I secretly hope that Derrick has a great year, too.

He deserves it.

With that being said, I want to hear your thoughts:

Do you think Derrick Rose gained five inches on his vertical?

And if so, what would you have done to help him get there?

I look forward to your thoughts and feedback below!

Stay strong

MR