As everyone knows, I’m a huge fan of powerlifting. It has provided a great link between my athletic career and my love of strength training. More importantly, I feel like the sport has molded me into the person I am today.

One of the most influential people for me when I was starting out was Louie Simmons. When I first learned about Louie, Dave Tate and Westside-style training, I printed off every single article I could get my hands on. To this day I still have binders full of powerlifting related articles written by these guys and their cohorts.

Quite simply, Louie, Dave and now Jim Wendler have all played a huge role in my thought process as a powerlifter, coach and athlete.

Now I know many people have a love/hate outlook on Louie, but I don’t think anyone can refute the fact that he’s dedicated his life to the sport of powerlifting and taking it to the next level.

One thing that Louie has discussed in numerous articles is the reverse hyper and how it helped him rehabilitate numerous back injuries. I’ve been thinking about this exercise for years; unfortunately, I’ve often come up with more questions than answers.

Some of the questions I’m hoping to answer today include the following:

– Are reverse hypers effective for the rehabilitation of low back issues?

– Will reverse hypers develop a strong posterior chain using the prescribed exercise technique?

– Are there alternative strategies that are safer and/or possibly more effective?

Please do not take it any of this as a jab at Louie Simmons. The guy has given more to the sport than just about anyone, and I have the utmost respect for him. The goal is not to disparage him whatsoever, but to critically examine the reverse hyper exercise, and to outline alternative techniques and/or exercise that could be safer and/or more efficacious.

Before we get into the guts of the newsletter, I want to make a few things clear:

– By powerlifting standards, I’m probably not considered “strong.” My best squat was 530 and my best deadlift was 535 pounds.

– Like many powerlifters, I have injured my back before. It’s never fun.

What I’m getting at here is that I’m not the strongest guy you’ll ever meet, and I’m definitely not bulletproof. My main reason for writing all this up is to help refine and optimize the training process.

If I can help someone hit a PR total, or just stay healthy over the long haul, then I feel like I’ve done my job.

The Promise of Reverse Hypers

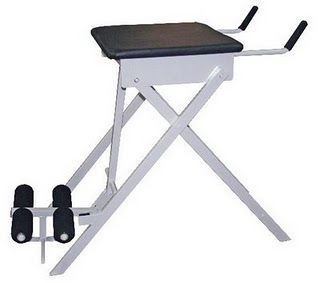

While you might happen to find one of these machines in your local gym, you’re much more likely to find them in a key club or powerlifting-based gym. Reverse hypers have been espoused for years to develop the muscles of the posterior chain, specifically the glutes, hamstrings and lower back.

Beyond the muscle-building effects, reverse hypers have also been touted as a great device for low-back rehabilitation, and I think that’s where I have some issues. Here are just a few of the quotes I’ve found from various sources when discussing the reverse hyper:

The Reverse Hyper is very therapeutic for the low back because it rotates the sacrum on each rep.

One other very important machine, the Reverse Hyper machine, will not only build the hamstrings, glutes, and spinal erectors but also traction the low back by rotating the sacrum and rehydrating the disks.

The real secret of this machine is that it tractions the vertebrae while you use it so it builds strength and works at restoration at the same time.

Exercise technique would include lying on the pad, grabbing the handles, and using the muscles of the posterior chain to extend the weight upwards. On the way back down, momentum is used to traction your back, and the weights are often allowed to come back to a point where the feet are underneath the face. From what I’ve seen, a lot of momentum is employed throughout the exercise.

When we look at the biomechanics of the exercise, I have some doubts as to just how safe it would be. Here are a few of my concerns:

1 – To begin, we know that loaded spinal flexion is a huge no-no. In fact, it’s one of the easiest ways to herniate a disc in your lower back! In the case of the reverse hyper, so-called “optimal technique” would involve not only a high degree of flexion in the lumbar spine, but a tractioning force as well. I cannot fathom how high the forces must be on the intervertebral discs and posterior elements of the spine and connective tissues.

2 – While most people should be queued to extend with their hips, I would imagine that many would simply extend via their lumbar spine instead. If you’ve seen most people move, you know that have very weak gluteals and cannot produce extension via their hips.

So instead of hip motion, you get repeated flexion and extension of the lumbar spine. Couple this with the fact that it’s all performed under load, and you make a bad situation worse.

3 – Finally, I know that many lifters have used this exercise to rehab their lower backs. While I don’t have the immediate stats in front of me, I believe something along the lines of 50% of all low back issues resolve themselves without any treatment or therapy.

It’s impossible to say what percentage of people who use a reverse hyper get “healthy” or not due to the inclusion of this exercise in their programming. Instead, the point I’m trying to make is that a lot of people get healthy in spite of what they do, not because of it. This is important to note, especially in the rehabilitation setting.

While gathering my thoughts on the topic, I decided to see what Dr. Stuart McGill has to say about the topic. Here are his thoughts (from his Ultimate Back Fitness and Performance” book):

The hip extension (reverse hyper) machine is an excellent trainer for hip extension but imposes a large posterior shear load on the back. It will create back troubles in some and should be considered with great caution.

A substitute exercise that I often see people recommend is a similar variation placed over a Swiss ball. McGill has thoughts on that as well:

The reverse back/hip extension exercise once again causes very high posterior shear forces on the back – it is not recommended.

If you ask me, that’s pretty direct advice from the most notable spinal biomechanist in the world today.

The Other Side of the Equation….

The question then becomes, if the spinal biomechanics don’t make sense, how does this exercise help some people get healthy? Could this in fact be an ideal exercise for some people, while a terrible one for others?

This is the discussion that Bill and I had the other day. If you haven’t read it before, this would be a good time to quickly read over my Hips Don’t Lie article.

Many powerlifters (and athletes in general) walk around in a position of anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar extension. If we want to get them back to a more neutral alignment, we need a program that emphasizes strength in the external obliques, glutes and hamstrings. The reverse hyper readily addresses two out of those three areas – by producing a stress that creates posterior tilt, we take someone who is in anterior tilt back to neutral.

Let’s dumb it down even further: If someone has extension-based low back pain, this exercise could be invaluable for helping to get their butt and hamstrings stronger. I may have some issues with the technical performance of the lift, but strengthening the glutes and hamstrings is a must at some point in the program.

In contrast, I can’t think of any situation where I would recommend this exercise to someone with flexion-based low back pain.

In my opinion, the effectiveness of this exercise boils down to the type of low back pain you suffer from.

Building a Better Reverse Hyper

The question then becomes, what can we do to optimize reverse hyper performance? Even if someone has extension-based low back pain, I’d have a hard time prescribing that they go through repeated cycles of lumbar flexion and extension.

To improve performance, we can start by eliminating the most stressful portions of the lift. Simply reducing the range of motion on the eccentric portion of the lift and not allowing lumbar flexion will go a long way to reducing shear forces on the back.

Next, as suggested by Bill Hartman, we could move to a prone-on-elbows position. This would put someone in a more neutral low-back alignment, and encourage a more hip-dominant lift.

Finally, we could take away the momentum, lower the weight, and make sure we’re using the appropriate muscle groups to do the work. I remember a discussion I had years ago with Brad Gillingham, where he mentioned he was using very lights weights and focusing on the hip extension portion of the lift. I could be wrong but I seem to remember him saying he was only using 50 pounds or so on the lift. This is pretty significant, because the guy has been powerlifting for close to 20 years and still routinely deadlifts well over 800 pounds in competition!

Conclusion

I’ve done my best to be un-biased and look critically at the evidence both for and against use of the reverse hyper. I think that, as is typically recommended/prescribed, the exercise has a very high cost:benefit ratio, and as such shouldn’t be employed in strength programming.

However, with some minor modifications, you have an exercise that not only spares the spine, but develops the glutes and hamstrings to a high degree as well. This is something that would benefit not only athletes, but your average day-to-day client as well.

The devil is truly in the details, but I’m hoping that this post not only leads to some improved powerlifting totals, but improved longevity and resilience regardless of your fitness goals.

But I’m also interested – what do you guys think?

Do you use reverse hypers? And if so, do you find them valuable to your training?

I look forward to your thoughts below!

Stay strong

MR