If you’ve been around athletics for any period of time, chances are you’ve seen the athlete who isn’t “in shape.”

If you’ve been around athletics for any period of time, chances are you’ve seen the athlete who isn’t “in shape.”

Whether it’s football, basketball, soccer, or something in between, they make a few runs up and down the field or court and they’re gassed.

Red faced, tugging on the shorts, and gasping for air like they’ve just been held under water against their will for the last 30 seconds.

And what’s even more baffling is that sometimes these athletes, outwardly, are the fittest looking athletes you can imagine!

So what gives?

Let’s start with a few definitions, just so we’re all on the same page. From there, we’ll talk about strategies and interventions to help these athletes out.

What You Need to Know

Let’s started with a brief definition of a few terms:

Resting Heart Rate (RHR) – How many times your heart beats per minute at rest

This one is pretty simple, but it’s also something that many coaches fail to assess or look at initially.

For most field or court sport athletes, I like their resting heart rate in the 50’s, or possibly even high 40’s.

When you have a lower resting heart rate, your heart is more efficient and effective. The less often your heart has to beat, the less energy it expends to supply your body with oxygenated blood.

When you have a lower resting heart rate, your heart is more efficient and effective. The less often your heart has to beat, the less energy it expends to supply your body with oxygenated blood.

When an athlete’s resting heart rate is too high, this is somewhat akin to having an energy leak biomechanically. Their body is working harder than it should be to perform a certain level of work.

On the other hand if resting heart rate gets too low, you begin to sacrifice speed/strength/power for greater aerobic fitness and economy.

If you’re a marathon runner, this is one thing.

But if you’re a field or court sport athlete, the goal is to have a mix of speed/strength/power, and the aerobic engine necessary to support high- and low-intensity exercise for prolonged periods of time.

If you want a full write-up on this topic, please check out previous article below:

You NEED Long-Duration, Low-Intensity Cardio

Anaerobic threshold (AT) – The point where you move from primarily aerobic metabolism to primarily anaerobic metabolism

There’s been a ton of talk about the anaerobic threshold and what it really is, but here’s the most layman definition I can give you:

Anaerobic threshold is the point where a combination of local factors (i.e. altered blood pH, hydrogen ion build-up, etc.) and central factors (i.e. your brain) alter and regulate your body’s ability to maintain prolonged, high-intensity exercise.

And while most focus on the local factors, my good friend Eric Oetter’s presentation at the BSMPG last May really showed how important the brain is in managing and interpreting fatigue.

On a primal level, your body probably isn’t a huge of anaerobic metabolism.

Sure you can tap into it when necessary, but when you rely on anaerobic metabolism your body has a lot of ways of telling you:

“Hey bro – I don’t like this. Let’s tone things down a bit (or stop all together)!”

If you’ve played sports at any level, you know what this feels like, too.

You’re cruising along, and then for some reason, you get a fire lit under your ass and you start running around like a crazy person.

After a while, you’re sucking air and your thighs are burning like there’s no tomorrow.

Next thing you know, even if you wanted to continue running around like this (which you probably don’t, because it sucks and it’s uncomfortable), your body is going all Roberto Duran “No Mas” on you, and you’re forced to cool your jets.

Next thing you know, even if you wanted to continue running around like this (which you probably don’t, because it sucks and it’s uncomfortable), your body is going all Roberto Duran “No Mas” on you, and you’re forced to cool your jets.

Now that we’ve covered resting heart rate and anaerobic threshold, let’s discuss our final term.

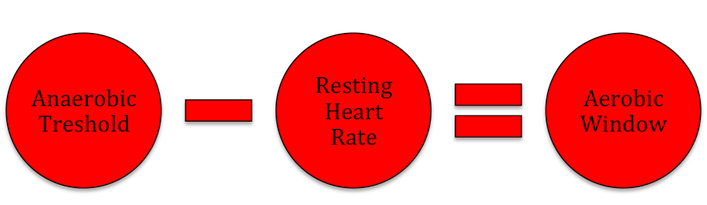

The Aerobic Window – The difference (or gap) between your resting heart rate and anaerobic threshold

This is simple math:

Here’s a visual that I think will help, too.

Here’s a visual that I think will help, too.

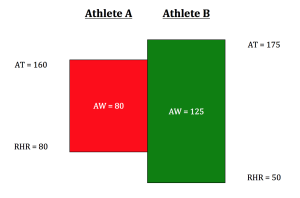

If Athlete A has a resting heart rate of 80 bpm, and his/her anaerobic threshold is 160 bpm, then they have an aerobic window of 80 bpm.

If Athlete A has a resting heart rate of 80 bpm, and his/her anaerobic threshold is 160 bpm, then they have an aerobic window of 80 bpm.

If Athlete B has a resting heart rate of 50, and his/her anaerobic threshold is 175, then they have an aerobic window of 125 bpm.

My goal with most athletes is to widen this window, but first let’s discuss why this is important.

“Don’t I Just Go Hard All the Time?”

Of course, the easy answer here is “No” – but rather than stop there, here’s a quick Pros and Cons list of the aerobic vs. anaerobic energy systems.

The anaerobic or glycolytic energy system is great for those times when you have to go really hard for a short period of time.

The downside here is that fatigue builds up much quicker as you pass over anaerobic threshold. Not only does fatigue accumulate, but the limits of anaerobic energy production (1-2 minutes) are quickly realized as well.

So while it’s cool to be explosive and powerful, there’s a finite amount of time when this is possible.

On the other hand, the aerobic energy system takes a bit longer to get cranking at full capacity, but your ability to produce energy is very robust.

While your glycolytic system will peter out after 1-2 minutes, your aerobic energy system can produce energy for hours on end.

Quite simply, the bigger aerobic engine you can build, the less likely you (or your athletes) are to fatigue during a game or match.

In almost any given sport, there are going to be times when you cross over into glycolytic metabolism, and that’s ok. When you want/need to go hard, you need to have that capacity.

But if you fail to train the aerobic system effectively, once you go glycolytic, it’s as though you can’t get out of it.

Your heart rate struggles to come down in between runs, and each ensuing run or effort drives you back over your anaerobic threshold and into anaerobic metabolism.

So how do we address this?

Easy – we work to widen your aerobic window!

Widening the Aerobic Window

The easiest way to do this is think of it as a two-step process:

- If resting heart rate is high, work to lower it first.

- Push-up, or raise, anaerobic threshold.

Resting Heart Rate

I kid you not when I say that we’ve assessed professional and collegiate athletes with resting heart rates in the 70’s and 80’s.

One kid in particular came into IFAST as a winger on his college soccer team with a resting heart rate of 84 beats per minute!

While chatting with him one day at the gym, I basically told him what his game looked like without ever seeing him play.

He was really fast and explosive, but he made 3-4 runs and then he was gassed!

The goal here is to create central adaptations at the heart, primarily by increasing left ventricle eccentric hypertrophy. Again, you can read about this in my low-intensity cardio article, and Mark McLaughlin covers it here as well.

Eccentric hypertrophy increases the width or diameter of the left ventricle, and therefore a greater volume of blood can move into (and out of!) the left ventricle of the heart.

And if you can push out more blood with each heart beat, your heart doesn’t have to pump as often. This is efficiency and economy at it’s finest.

Plus, I’m a big believer in going for the easy gains first. Why start with high-intensity exercise when you can see massive changes in how an athlete feels and performs simply by adding in low-intensity training mediums?

The bottom line is this: If you have an athlete with an exorbitantly high resting heart rate, fix that first.

Anaerobic Threshold

Once resting heart rate is under control, the next goal is to address anaerobic threshold.

Even if someone has a lower resting heart rate, they could still be very anaerobically dominant during exercise.

I’ve seen athletes with resting heart rates in the 50’s, but you make them run for more than a minute or two at a decent clip and their heart rate is in the 180’s.

These athletes have typically been trained with high-intensity methods for months (or years!) on end, and thus can’t produce energy aerobically when intensity gets cranked up.

These athletes have typically been trained with high-intensity methods for months (or years!) on end, and thus can’t produce energy aerobically when intensity gets cranked up.

Instead, they run hard for a few minutes, or make a few hard runs, and they immediately shift to anaerobic metabolism, because that’s all they have to rely on!

So the next question becomes, how do you determine anaerobic threshold?

At IFAST we typically use a Modified Cooper’s test. Have the athlete run, bike, row, etc., for six minutes. The goal is to go as hard and as fast as you can for that six minutes.

Take their heart rate every minute on the minute, and then average their heart rate over the six minutes to determine their anaerobic threshold.

Once you’ve determined AT, it’s time to program accordingly.

Perhaps my favorite intervention to drive up anaerobic threshold is called aerobic power work, or threshold training. I originally learned about them from Joel Jamieson, but have since seen them used time and again from the likes of Dave Tenney, Patrick Ward and numerous other.

The goal of aerobic power work is to spend a certain amount of time (1-5 minutes) hanging out around anaerobic threshold, without crossing significantly over into it. From there, take a similar (1-5 minutes) amount of rest.

By constantly hanging out around AT without crossing over into primarily anaerobic metabolism, you raise your ceiling for aerobic metabolism.

Or in our case, push-up the top of that aerobic window.

And when you push up AT, you can make more high-intensity runs while still relying on aerobic (vs. anaerobic metabolism).

Summary

Widening our aerobic window allows our athletes to be more efficient and economical at low-intensity work.

And on the other end of the spectrum, it allows us to stay in our happy place of aerobic metabolism longer as well.

Remember, you not only have larger energy stores available via aerobic metabolism, but you can mitigate fatigue for longer periods of time as well vs. high-intensity or anaerobic training.

At the end of the day, the goal is to not only create faster/stronger/more powerful athletes, but athletes that are resilient and can go for extended periods of time as well.

Work to widen the aerobic window of your athletes, and I guarantee they’ll be performing better (and longer!) than ever before.

All the best

MR

P.S. – If you want to learn more about energy system programming for clients and athletes, I outlined this (and much, much more) in my Complete Coach Certification.

If you haven’t checked it out yet, it’s definitely worth a look!