Over the past year I’ve given my “Facts and Fallacies of Corrective Exercise” presentation approximately one billion times.

Over the past year I’ve given my “Facts and Fallacies of Corrective Exercise” presentation approximately one billion times.

Okay maybe that’s a slight exaggeration, but I’ve definitely given it a lot!

One of the topics I always come back to is the topic of scapular stability, and lately, I’ve been asking myself more and more questions. This is definitely a good thing; the problem is, I keep coming up with fewer and fewer black and white answers!

A Quick Recap on the Joint-by-Joint Approach

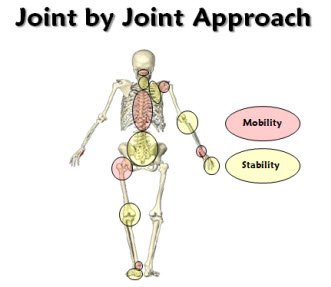

Mike Boyle is well-known for popularizing the joint-by-joint approach to training.

The premise is simple: The major joints in your body alternate or flip-flop with regards to whether they need more mobility training, or more stability training.

According to the joint-by-joint, the ankle typically needs more mobility, so the joint above (the knee) and the joint below (the foot) need more stability-focused training.

In case you are unfamiliar with the concept, please see the graphic below.

If we follow the joint-by-joint approach to the scapulae, it tell us that the scapulae needs more stability, so the joints above and below (i.e. the thoracic spine and shoulder) need more mobility.

But as with all things, I just don’t think the answer is quite that black and white. And it really all begins with one very simple question…

What is stability?

I’m a big fan of the following quote:

“Stability is control in the presence of change.”

– Charlie Weingroff

However, when most people think of scapular stability, I think the natural tendency is to focus on static stability.

Think about how you set-up on a bench press. We all know that if your goal is to maximize your performance on the bench, you need to be as stable as possible through your upper body.

So what do you do?

Your pin your shoulder blades back and down, cranking the hell out of your rhomboids, lower traps, etc.

Again, this is static stability. In other words, once your scapulae are set they don’t move. If your goal is to bench press 500 or 1,000 pounds, this is obviously important.

But is this what most of us should be focusing on?

If you work with athletes, fat loss clients, etc., I would argue that dynamic stability is far more important and useful in everyday life.

Dynamic stability is more true (at least in my opinion) to what Charlie is defining as “control in the presence of change.”

Being able to put your shoulder blade in the right position and controlling it while pressing something overhead, performing a chin-up, or throwing a baseball is of critical importance.

The issue here is that many people have very poor active scapular stability, for at least two primary reasons

Let’s look at each of them in depth.

Stability Issue #1: Poor Thoracic Spine Position

While I’ve mentioned this numerous times before, it bears repeating:

If your thoracic spine is in a poor resting alignment, your scapulae will never be in the right position.

Read that again: If your thoracic spine is in a poor resting alignment, your scapulae will never (ever, ever, ever) be in the right position.

When we assess people at IFAST, we typically see one of two aberrant thoracic spine postures:

- The typical excessively kyphotic/computer guy type posture, or

- The excessively flat thoracic spine.

I think we all know an excessive kyphosis when we see one. There is either an excessive apex of the kyphosis, or the kyphosis itself is longer than it should be.

When a client comes to you with an exaggerated kyphosis, it’s standard to see winging of the inferior border of the scapula.

I’ve talked about this ad nauseum in the past, so I’m not going to belabor the point here.

A postural flaw that we don’t discuss as often is that of an excessively flat thoracic spine. When viewed from the side these clients look incredibly thin through their thorax and ribcage.

While I see it more often in women, you can definitely see it in men as well.

Furthermore, when observed from the back, you tend to see the entire medial border of their scapulae.

Back in the day we’d just diagnose this person as having a weak serratus and go on about our business, but this isn’t necessarily the case.

Instead, what we need to do is restore some degree of flexion through the thoracic spine.

If you look at the anatomy of the scapulae, there is a natural curve or arc to it. When you have a normal/natural kyphosis, the scapulae lays flat against the thoracic spine.

If you were to run your hands across their upper back, you shouldn’t be able to detect the bony prominences of the scapulae.

In contrast, a client with a flat thoracic spine has very obvious bony prominences on their scapulae. When the t-spine is too flat, the curved scapulae literally has nothing to “rest” on, which makes its bony landmarks much more prominent.

If your goal is to have adequate scapular stability, it all begins with having a natural and normal amount of kyphosis through the thoracic spine.

Too much, or too little, and your scapulae will never be as stable as it should be.

Write this down:

You must know the resting position of your body, and in this case, your thoracic spine. If you start randomly stretching/activating/strengthening without knowing position first, you’re doing it wrong!

Stability Issue #2: Poor Active Scapular Stability

Once you’ve restored a normal curvature through the thoracic spine, it’s time to focus on dynamic stability at the scapulae.

When assessing clients, it’s very easy to pick out those who have performed tons of bench presses and rows. If you ever get the chance to evaluate a powerlifter, have them perform this simple test:

When assessing their posture from the back, simply have your clients place their hands on their hips.

If the scapulae wing away from the t-spine, or they try and “pin” their shoulder blades together it’s indicative of what we’d call rhomboid dominance.

Instead of the serratus and lower traps kicking on to a slight degree, the rhomboids “pull” the scapulae back and/or off the rib cage.

To improve dynamic stability, it’s important to train stability in a variety of planes/movements. I’m not as big a fan of the old-school I’s, T’s and Y’s as I used to be, but they can definitely help teach position and motor control early-on.

I hope you’re probably familiar with basic training terminology that breaks movement patterns down like this:

- Horizontal Press (i.e. push-up variations, bench press variations, etc.)

- Horizontal Pull (i.e. rowing variations)

- Vertical Press (i.e. overhead pressing variations)

- Vertical Pull (i.e. chinning variations)

When you start to rebuild a stability pattern at the upper extremity, the horizontal options are typically the safest best. When pressing or pulling horizontally there are fewer mobility and stability demands versus going overhead.

Furthermore, starting with closed chain exercises (i.e. push-ups and inverted rows) and then progressing to open chain exercises (i.e. bench presses and chest supported rows) is superior early on in a program.

Something that is rarely talked about in coaching and training circles is the role of the ribcage when training the scapulae. A critical component of scapular stability is locking down the trunk/rib cage and allowing the scapulae to move on a stable ribcage and thoracic spine.

Think about it like this: If you’re doing a push-up, allow the shoulder blades to fall together natural when lowering, and focus on actively pushing your body as far away from the floor as possible on the overcoming portion.

On an inverted row, think about actively lengthening through the upper back and allowing the scapulae to glide around the rib cage when lowering, and think about squeezing the shoulder blades together at the top.

In both of the above examples, the rib cage should be stable throughout, while the scapula is free to protract and retract. If you’re having a hard time envisioning this, hopefully the video below will help.

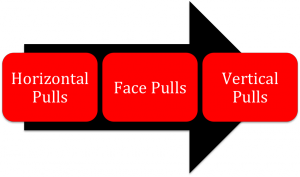

Another progression that we’ve had great success with here is something along these lines:

By following this progression, you minimize mobility and stability demands on the shoulder, while starting to re-build effective stability patterns. If used in conjunction with a smart corrective warm-up and exercise progression, you should be moving significantly better in no time.

Last but not least, I’m definitely not saying that pressing is a bad thing. On the contrary, I think pressing can help improve stability and control at the shoulder joint.

However, we need to be judicious in our approach.

Again, consider starting with horizontal, closed-chain movements (i.e. push-ups) and moving to overhead work over the course of a few weeks or months. I know I’ll catch some heat for saying this, but I think more people can/should be overhead pressing, but they need to have the foundation to do it safely and effectively.

Even if I never intend to load someone by pressing them overhead, I’m still going to train them biomechanically as if I will.

That means improving their thoracic spine position, scapular stability, and dynamic rotator cuff strength are going to be integral components of their programming. I may never actually load the pattern, but I want them to have the underlying movement qualities necessary to do so safely and effectively

Summary

Scapular stability may not be a myth, but it’s definitely not as easy as pinning your shoulder blades back and together and hoping for the best.

Instead, scapular stability comes down to two primary components: Good thoracic spine positioning, and training in multiple planes for dynamic scapular stability.

Focus on both of these critical areas and you’ll be rewarded with healthier joints and improved performance to boot!

Stay strong

MR