It feels like athletes today are getting injured at a higher rate than ever before.

But what’s even more saddening is these injuries aren’t just coming at a faster clip, but they appear to be more serious as well.

Want some cold, hard data?

Through Week 7 in the NFL there have been 40 torn ACL's & 32 ruptured Achilles!

— ACL Recovery Club (@ACLrecoveryCLUB) October 27, 2016

I’m a big believer that injuries are multi-factorial. For example if someone has a large “Q-Angle” for their knee, that’s not the only reason they tear an ACL.

Or just because someone has poor “quad:hamstring strength ratios” that that is the sole reason they end up with a hamstring pull.

After watching sports for my entire life, and working in the industry for 16 years now, I can tell you I see a few common threads that absolutely contribute to the increase in injuries.

I also believe that you can “bucket” injuries into primary areas:

- Athletes have lost the ability to flex and “bend,”

- Athletes have lost their ability to absorb and reduce force (i.e. they’ve got poor “brakes”), and

- Athletes don’t have the work capacity to meet the needs and demands of their sport.

Let’s look at each of these buckets in more depth, and provide a few answers to help build stronger, healthier and more resilient athletes.

#1 – They Can’t Bend

Imagine a running back in football coming in hard to a cut.

He sees a linebacker bearing down on him, and decides his best plan of attack is to plant, cut, and go in the opposite direction.

So he goes hard into his cut, but his system doesn’t allow him to bend at the hips, knees and ankles to absorb the force.

So instead of bending, he breaks – in this case, he tears his ACL.

Now here’s where things go beyond basic biomechanics. As human beings, we’re constantly in a state of flux.

Our body is constantly interpreting and responding to the environment and stimuli around us. All the while, it’s making small changes to fine tune our system to keep us in homeostasis.

Now here’s the bad news: We’re more stressed out, anxious and chronically inflamed than ever before.

But what does all this stress and inflammation do to our body in a biomechanical sense?

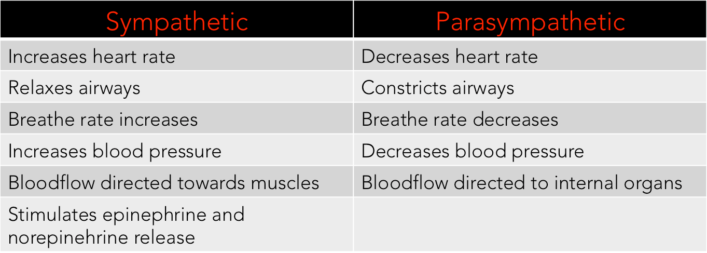

Excessive stress and/or inflammation drive a sympathetic response: We go into fight-or-flight mode, priming our body for survival by locking ourselves in the sagittal plane.

If we see a bear in the woods, we want to have this sympathetic response, and we want to lock ourselves in the sagittal plane.

We begin to breath heavy, our heart rate elevates, and blood flow is re-directed to our muscles. We also lock ourselves up so that we can run fast in a straight line and get the hell out of there!

And while that’s all well and good if we’re running from a bear in the woods (or pushing PR’s in the gym), it’s a huge problem if we can’t turn our sympathetic nervous system down throughout the course of the day.

I liken our autonomic nervous system to a volume knob on your radio. If you’re listening to Pantera and trying to push heavy weights, you want it cranked up to an 11.

But if you’re chilling with your lady listening to Al Green, the 11 isn’t really appropriate.

Better dial it back to a 3 or 4 there playboy.

It should come as no surprise, but this is how things work with regards to physical preparation as well. There isn’t right or wrong, there’s a “right-time and right-place,” where context actually matters:

- We need extension to accelerate, to run fast in a straight line, or to push an opponent off us.

- We need flexion to decelerate, change levels, and demonstrate mobility.

If you don’t have the ability to flex, you lose the ability to change levels.

Try this simple trick:

Stand up and assume a squat stance. Put your hands by your shoulders you’re going to back squat, and arch your back while puffing your chest out.

Take a big breath of air in, and squat as low as you can. Gauge not only how deep you can squat, but also how it feels.

Now let’s flip the script. Place your hands out in front of you and reach long. Exhale and allow your ribs to come down.

Now squat as low as you can, and gauge your depth and how much tension you perceive.

Pretty cool, huh?

Did I just increase your mobility?

Or did I simply allow you to access the mobility you already have?

Now let’s take this to sport. We’ve all heard a basketball or baseball coach yelling at an athlete to “get his butt down.”

But what if the athlete simply can’t do that?

What if they are so stressed out, i.e. so extended, that their system can’t perform that task?

It doesn’t matter how many times you yell at an athlete. Until you address the underlying stressors and restore flexion to the system, you’ll never get them into the positions that you want.

How to Fix It!

So how do we go about fixing it?

Instead of dealing with the root cause, we look at an athlete and simply say:

“This guy’s too stiff – he just needs more mobility training. Let’s have him do Yoga for a month and it should get better.”

It’s like trying to use a Band Aid to cover an aorta rupture; it’s just not going to stick!

The easiest way to address this sympathetic dominant/biomechanically extended pattern is to teach our athletes how to flex. And the easiest way to teach an athlete to flex is to teach them how to exhale.

Exhalation drives flexion. It restores a more optimal relationship between the lower rib cage and pelvis, which allows the body to get out of “fight-or-flight” mode.

Furthermore, once that flexion occurs, you start to give the body options again. It allows the athlete to get out of the sagittal plane, and (hopefully) restores motion in the frontal and transverse planes.

So learning to exhale and drive flexion is a great starting point. But we have to go deeper.

With all of my athletes, I try to have a discussion about the performance pyramid.

I put a big emphasis on the bottom level, which is their foundation.

- Are they eating healthful foods that will nourish and fuel their body?

- Are they getting enough deep, restful sleep?

- Are they managing their stressors outside the gym?

Failure to address these issues early-on will not only negatively impact their ability to flex and bend, but their recovery as a whole as well.

So that inability to bend is a huge issue, and it directly impacts this next element as well…

#2 – They Don’t Have Brakes

When we lock ourselves in the sagittal plane, not only does it restrict our ability to demonstrate mobility and change levels, but it also puts us a in a constant state of propulsion.

Try this:

Stand up and arch your back hard and puff your chest out. Where does your weight shift?

As you can see and feel, that extension drives us forward. Again, this is what allows us to accelerate, run fast, and jump high.

But what if our goal is to slow down?

To come into that cut hard, absorb the force, and then explode back out of it?

As you can see, Point #1 and Point #2 go hand-in-hand. If you can’t bend, your body is not in a position to absorb force.

But it actually gets worse, because so much of the training that we do in the gym, or on the track, only reinforces this.

We put all our stock and value on numbers – whether it’s a faster 40, a bigger vertical jump, or making the squat record board.

It’s sad, but the value we place on ourselves as “coaches” revolves around our ability to produce force, while putting little (or no) emphasis on force absorption.

The speed, strength and power work that we’re doing absolutely has value, but we need to ask more from ourselves as a profession.

How do we develop a program that isn’t based solely on numbers and production, but rather looks to build a fast, strong and resilient athlete?

How to Fix it!

Our primary goal should be to restore flexion. If you can’t flex, then your body will always be in a state of propulsion.

The easy answer here is to work on the biomechanical system and incorporate resets, exhales, and smart programming. The bigger picture, again, focuses on stress reduction and getting all of the body’s systems working at a higher level.

The second step should be to emphasize deceleration and force absorption at periods of time throughout the year.

Chances are as movement quality improves (via improved flexion), how the body expresses movement will be different as well.

Your squats will be “squattier” and more upright.

Your hinges will be more “hingy” and you’ll be better able to access and load the hamstrings.

As such, you’ll need a period of time where you focus on slower, controlled movement, to help an athlete “feel” where they are in space.

Once motor control is improved, then you move on to deceleration-based exercises that increase the speed.

Instead of performing a squat, you could move to an altitude landing.

Instead of a lateral lunge, you could move to a lateral jump and hold.

The goal here is to take those elements of movement quality and control, and now to add that element of speed to the equation.

Once an athlete can perform in a slow-and-controlled fashion, and they can absorb force, now it’s time to let loose and allow for the fullest expression of athletic movement.

But I can’t emphasize this strongly enough – take the time to build an athlete right the first time.

Don’t skip steps.

Don’t get impatient.

Do it right the first time, and you’ll be rewarded with an athlete that performs at a high level for years to come.

#3 – Their Work Capacity Sucks

The final reason that athletes get injured is simple:

Their work capacity sucks.

We can look at this as an extension (pun intended) of the above issues.

The athlete gets stressed out and defaults to the sagittal plane.

Now they lose their ability to bend, and they’re locked in a state of force production – effectively wrecking their ability to absorb force.

By defaulting to this extension-based pattern, it also forces us to rely excessively on the anaerobic (versus the aerobic) energy pathways.

Now there are obviously times where the athlete is solely to blame.

Now there are obviously times where the athlete is solely to blame.

If an athlete does nothing all off-season and then reports to camp overweight and out of shape, they have no one to blame but themselves.

However, if an athlete is working their tail off and the methods that are administered are faulty, the blame lies solely on the coach.

One of the biggest issues we have these days in coaching is a poor understanding of physiology, and the energy pathways we rely on in competitive sport.

The aerobic energy system has been vilified for years, even though it’s primary jobs are:

- To create energy for extended periods of time (i.e. basketball, soccer, rugby, Aussie rules football, etc.),

- To refuel our anaerobic system so that we can be fast and explosive when we need to be.

This is why I’ve been such a huge proponent of Joel Jamieson’s work for years now. Joel has done a fantastic job of showing the interplay between the various pathways, and how to maximize the performance of each system

How to Fix It!

Getting serious about your energy system training is a HUGE step in the right direction. Kudos to you for taking the steps necessary to elevate your game.

The downside here is this: There’s no way I can do this topic justice in a few short words!

Instead, I would highly recommend you check out the energy systems section of my website. The first page alone will give you a ton of food for thought, and help you start building better conditioning programs for your athletes.

Beyond that, make sure to listen to the podcasts I’ve done with Joel Jamieson which are also featured on that page. One thing that Joel harps on is maintaining movement integrity/quality when fatigued.

Remember, as an athlete fatigues they will be more likely to “default” to their sagittal plane. And the more sagittal they get, the more anaerobic they get.

The more anaerobic they get? Well, you see where I’m going with this – it’s a vicious cycle.

Focus on not only building capacity, but doing so while maintaining high quality movement throughout.

Summary

This article took way longer than I expected, but that happened for two reasons:

- This is a really broad topic and it’s hard to narrow the scope, and

- I wanted to be as clear as possible while writing it.

When it comes to training, there are no absolutes.

There isn’t black-and-white, right-or-wrong. It’s all grayscale, continuums, and educated guesses.

However, the three reasons I gave above are absolutely playing a role in the injury rates we see today.

And if we’re serious about growing as a profession, and helping as many athletes as possible along the way, we need to be looking as deeply as possible into these three areas of physical preparation.

Teach your athletes to bend.

Teach your athletes to absorb force.

And give your athletes sport-specific work capacity.

I guarantee if we can do this, that our next generation of athletes will be more resilient both during, and after, their playing career.

All the best

MR